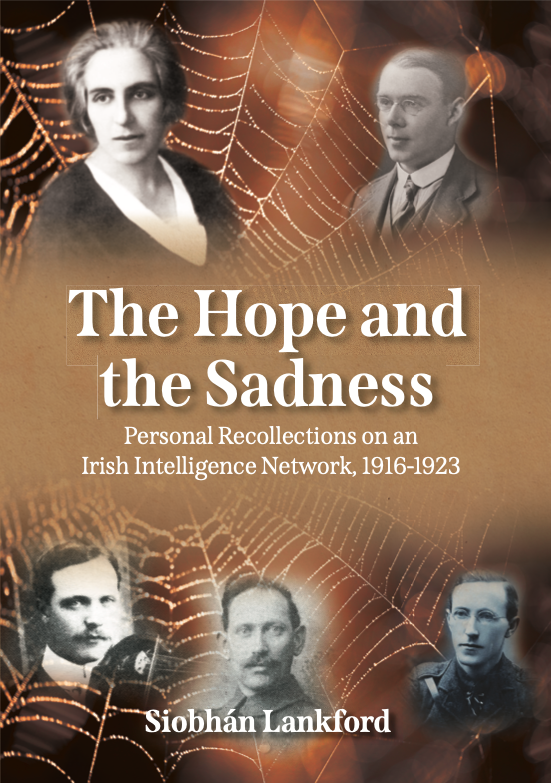

The Hope and the Sadness

Personal Recollections of an Irish Intelligence Network, 1916 - 1923

Siobhán Lankford’s book, The Hope and The Sadness, first published in 1980, is her personal recollection of a long and varied life. She was three weeks old when her father Patrick Creedon was released from prison, having served a sentence for defying a court order by returning to his farm from which he had been evicted. Educated at a local hedge school and imbued with a great sense of the Gaelic tradition, Patrick coloured his daughter’s childhood with tales of Famine times, the Fenians and Land League struggles. From a young age she was sensitively aware of the gift of a centuries old heritage: the delights of the land and of her place; the treasures of lore and language; the value of family and neighbours. Her reminiscence here of a rural girlhood at the turn of the 19th/ 20th century rings in an authentic voice, written in lyrical style, and vividly coloured by the eye of one who learned early the joy of keen observation.

That early honing of observation would continue to sustain the commitment of Siobhán’s long and interesting life. By the outbreak of WW1 she was working in Mallow Post Office, well placed to observe life around her in a town that was an important military and police centre, a railway junction, a point on the main cable and telegraph routes and home to a strong loyalist population. By the time news of the Easter Rising in Dublin spread around the town, Siobhán was already familiar with the activities of the Volunteers in Cork and Mallow and she was soon recruited into the intelligence network organized by Tomás MacCurtain. Her story then becomes the personal testimony of a woman who served as an Intelligence Officer with the Volunteers at local level in Cork during the revolutionary period, 1916-23, with an effectiveness that frequently impacted on decisions made at national level.

The Epilogue in this edition, written by her son, Doctor Éamon Lankford, gives an account of the author’s later life as Materfamilias and cultural nationalist who engaged productively into her old age with the cultural life of Cork City.

An appendix detailing the author’s protracted dealings with The Military Pensions Board shows how a strategic, courageous Intelligence Officer became a lost woman in the male-dominated bureaucracy of the new Irish State.

‘A modest telling of a remarkable story that had to be told, and in the telling she incidentally reveals

herself as a person of very high courage and unusual intelligence, observant and appreciative of her

circumstances and her company wherever she finds herself.’

From a review by the late Pádraig Ó Maidín, Cork County Librarian of the 1980 edition of

The Hope and The Sadness.

‘Miss Creedon has given exceptional service in the capacity of an Intelligence Officer, doing more than one

man’s duty and taking more than a man’s risks in carrying out tasks which called for a high standard of courage,

steadfastness and discretion. That work was of the highest value to the I.R.A. and to the nation and contributed

much to the success of the I.R.A. in the southern counties’.

Florrie O’ Donoghue, Adjutant to Tomás MacCurtain, Cork 1 Brigade from 1917.

‘A most remarkable and highly important coup by Miss Creedon during the Conscription scare was her getting hold of

the Enemy’s Military Plans in the event of Conscription being applied. I am personally aware of the regard Michael

Collins had for Miss Creedon, also Richard Mulcahy. It is hardly necessary to point out that Liam Lynch and his

staff regarded her in no less a light’.

Major General Liam Tobin, National Director of Intelligence I.R.A. 1919-1921.

Publication of this work is supported by Cork County Council Commemoration Grant Fund 2020.